A few weeks ago, I shared a moment on LinkedIn that sparked this project. I was in a museum, scanning a QR code to get an exhibit guide. Instead of information, I got a spinning wheel, no signal, no content, just an empty screen. Around the same time, I’d had a similar issue in a restaurant trying to access a menu.

That raised a simple question: what if the content wasn’t somewhere else, but right there in the image itself?

I built a quick prototype to test the idea. A large image could store enough for a document, an audio file, even a small app. With a proof-of-concept iOS app, I could encode any file into an image and decode it instantly. No backend. No network. No “404”. Just fast, resilient access to information, even offline.

That experiment became the seed for ColGlyphCode.

Building on a Great Foundation

QR codes are one of the quiet revolutions of the digital era. They’re reliable, efficient, and endlessly versatile. ColGlyphCode doesn’t try to replace them — instead, it builds on their foundation, taking the same principle of compact, scannable data and pushing it further with colour and glyphs.

The aim is to create codes that are both machine-readable and visually distinctive. Instead of monochrome squares, ColGlyphCode uses a mix of alphanumeric characters, colours, and rotations. The result is a format designed for offline-first access that also blends into designs, packaging, or cards more gracefully than standard QR.

The Practical usage

The goal is not to compete with QR codes where they already excel, but to offer a new option in cases where resilience or offline capability matter most.

Imagine a rural visitor centre with patchy mobile signal. Instead of scanning a QR code that points to a website, visitors scan a ColGlyphCode on a leaflet and instantly receive the entire audio tour — directly from the image itself.

At a conference, a badge could carry not just a link to a profile, but an embedded vCard, slides, or even a demo video. In fieldwork, a few ColGlyphCode sheets could replace bulky binders by storing dozens of pages of critical information in digital form.

Even at modest settings, a single A4 sheet can hold 160–190 KB of usable payload — enough for 20–40 pages of Word text. By tiling grids across the page, that capacity can scale to ~1 MB per sheet, which is enough for a complete visitor guide or training manual without printing stacks of paper.

Under the Hood

ColGlyphCode is built around two core design choices: a print-ready colour palette and a rotation-safe glyph alphabet. Together, they form the backbone of how information is stored and recovered from the codes.

For colour, the system avoids exotic hues and instead relies on what every printer can reproduce reliably: the four CMYK inks. From these, we derive a base palette of eight clear classes — white (paper), black (pure K), cyan, magenta, yellow, and the three stable two-ink combinations (red/orange from magenta+yellow, green from cyan+yellow, and blue/purple from cyan+magenta). This set is deliberately limited but robust, ensuring the colours remain distinct under varying lighting and print conditions. To further improve reliability, each sheet carries a calibration strip with swatches of all eight colours. When scanned, the reader uses these swatches to dynamically adjust its thresholds, compensating for any environmental shifts.

Alongside colour, the second dimension of encoding comes from the glyph alphabet. Instead of abstract geometric shapes, ColGlyphCode uses a carefully curated subset of familiar letters and numbers. This choice makes the codes more approachable to the human eye while still highly machine-readable. Ambiguous characters are deliberately excluded — for example, “O” and “0”, or “6” and “9” — because they become difficult to distinguish when rotated. What remains is a working set of roughly forty glyphs: twenty uppercase letters, ten lowercase forms, and ten digits. Each cell in the grid can then express not only a glyph and a colour, but also one of four possible rotations (0°, 90°, 180°, or 270°), multiplying the number of unique states it can represent.

The result is impressive density. With forty glyphs, eight colour classes, and four rotations, each cell offers 1,280 possible states. In information terms, that equates to roughly 10.3 bits per cell. When printed at safe, real-world module sizes of half a millimetre to six-tenths of a millimetre, a single A4 sheet can carry around 173,000 cells. That translates into about 223 kilobytes of raw payload, or between 160 and 190 kilobytes of usable data once error correction is accounted for.

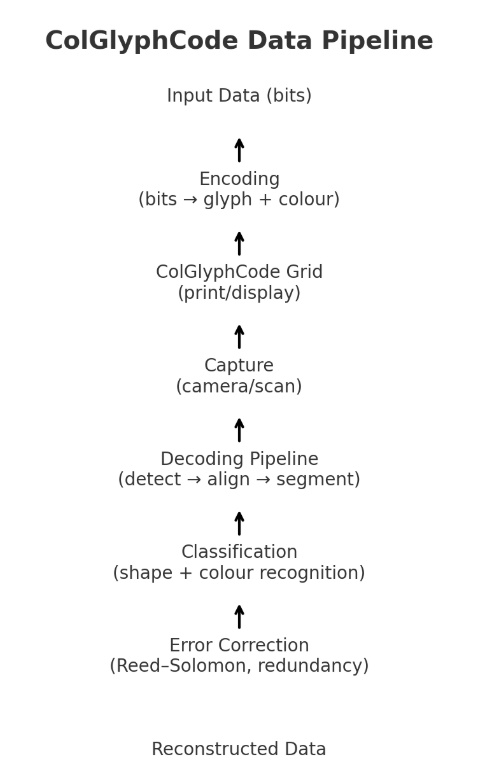

Error correction is vital, because no real-world print or scan is perfect. ColGlyphCode borrows the same Reed–Solomon coding techniques used in QR codes and optical media, which can recover data even if some symbols are blurred, colours shift, or small parts of the code are damaged. The decoding pipeline mirrors the QR process but with added complexity: the reader first detects finder glyphs and the calibration strip, then corrects perspective to square the grid, before segmenting individual cells. Each cell must be classified both for glyph shape and colour, after which Reed–Solomon error correction is applied to reconstruct the original payload.

ColGlyphCode stands on the shoulders of QR codes. It’s not about replacing them but about asking: what if we add colour, shape, and offline capability to the mix?

It’s still early, but the potential is exciting. I’ll share more as the prototypes evolve and the first tests roll out.

Leave a Reply